What's Happening to Boys and Men in Schools?

The Quiet Education Crisis No One Wants to Name

Noaman Farooq

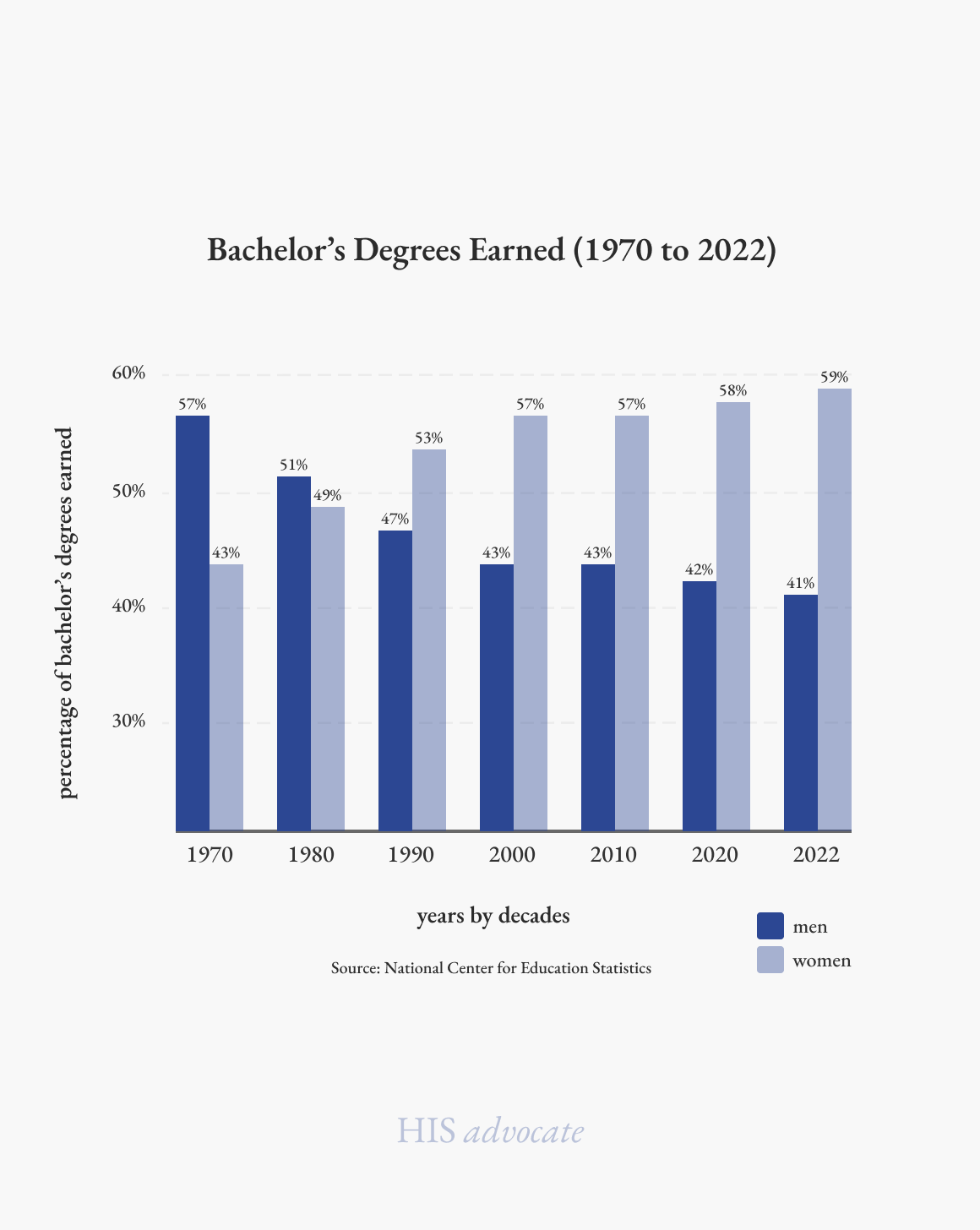

In 1970, 57% of bachelor’s degrees were earned by men, whereas women only earned 43%.1 Two years later, Title IX was passed to pave the way for greater educational opportunities for women. Since 2000, we’ve seen a surge of programs and incentives encouraging girls to enter STEM fields.23 As a result of educational advancement for girls and women, this led to financial stability for women across the country. In 2023, 45% of mothers were breadwinners,4 and in 2024, 49% of new businesses were started by women, a 69% increase from 2019.5

As we’ve continued to celebrate the achievements of girls and women, have we overlooked a generation of struggling boys and men?

Because this is what the data is telling us: boys and men are falling behind in education.

A Different Gender Gap

Different groups can have varying levels of school readiness. One might assume that the largest gaps of school readiness occur between racial or socioeconomic groups, such as White and Black children, or between middle- and lower-class families. While it’s true that these disparities exist between these groups, the largest gap occurs between gender. By age five, girls are fourteen percentage points higher in school readiness compared to boys.6

In other words, by the time boys enter elementary school, their disadvantage has already begun.

By fourth grade, boys are six percentage points lower in reading proficiency than girls, and by the end of eighth grade, this gap widens to eleven percentage points.7 It’s reasonable to assume that boys perform better academically by the time they reach high school. However, the data shows us otherwise.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which works with over 100 countries globally, conducts the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test, a survey issued every three years to test the knowledge of 15-year-old students in math, reading, and science. The results show that boys continue to struggle in these key subjects. They are 50% more likely to fail in math, reading, and science than girls (Reeves, 2022).8

Ranking high school students by GPA, boys account for the bottom two-thirds of the lowest scores, whereas girls account for the top two-thirds of the highest scores.9 In June of 2025, the American Institute for Boys and Men published research examining what ninth-grade boys and girls want to be when they’re 30. The most common response among girls (39%) was a career in HEAL fields (health, education, and literacy). And for boys, the most common answer was “don’t know” (34%).10

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when schools made the shift to an online learning environment, male students struggled with online learning, highlighting their vulnerability to disruptions in learning environments.11 Yet nothing was done to correct this disadvantage for boys. At the end of high school, or more specifically, the public education experience, seventy percent of valedictorians across the country are girls.12

Maybe there’s a glimmer of hope that finally, by college, male students level out and begin to catch up to their female peers.

If only this were true.

In 2022, 57% of boys immediately enrolled into college after high school, compared to 66% for girls. Not only are male students more likely to drop out, but college completion is lower for them overall: 35% of male students graduate from college, compared to 46% of female students.13 A final note about the COVID-19 pandemic: male students were seven times more likely to drop out of college compared to women during the pandemic.14

Recalling the previous statistic about the percentage of bachelor’s degrees earned by men and women in 1970, that number is nearly the same today, but now the gap has reversed. In 2022, women earned 59% of bachelor’s degrees, whereas men only earned 41%.15 In fact, since 1990, women have earned the majority of bachelor’s degrees in the United States. The graphic to the right illustrates the percentage shift in bachelor’s degrees over the last fifty years between men and women:

How can we understand this phenomenon of male students falling so far behind their female peers? Are girls just smarter than boys? Well, in this current system, yes, however this is because the current system favors the developmental timelines of girls over boys. To be clear; girls can struggle with sitting still, staying quiet, and focusing during class, but they’ve generally tolerated these demands better than boys have.

The core reason behind this education gap between girls and boys can be summarized in two words:

Neurological development.

The Brain Gap

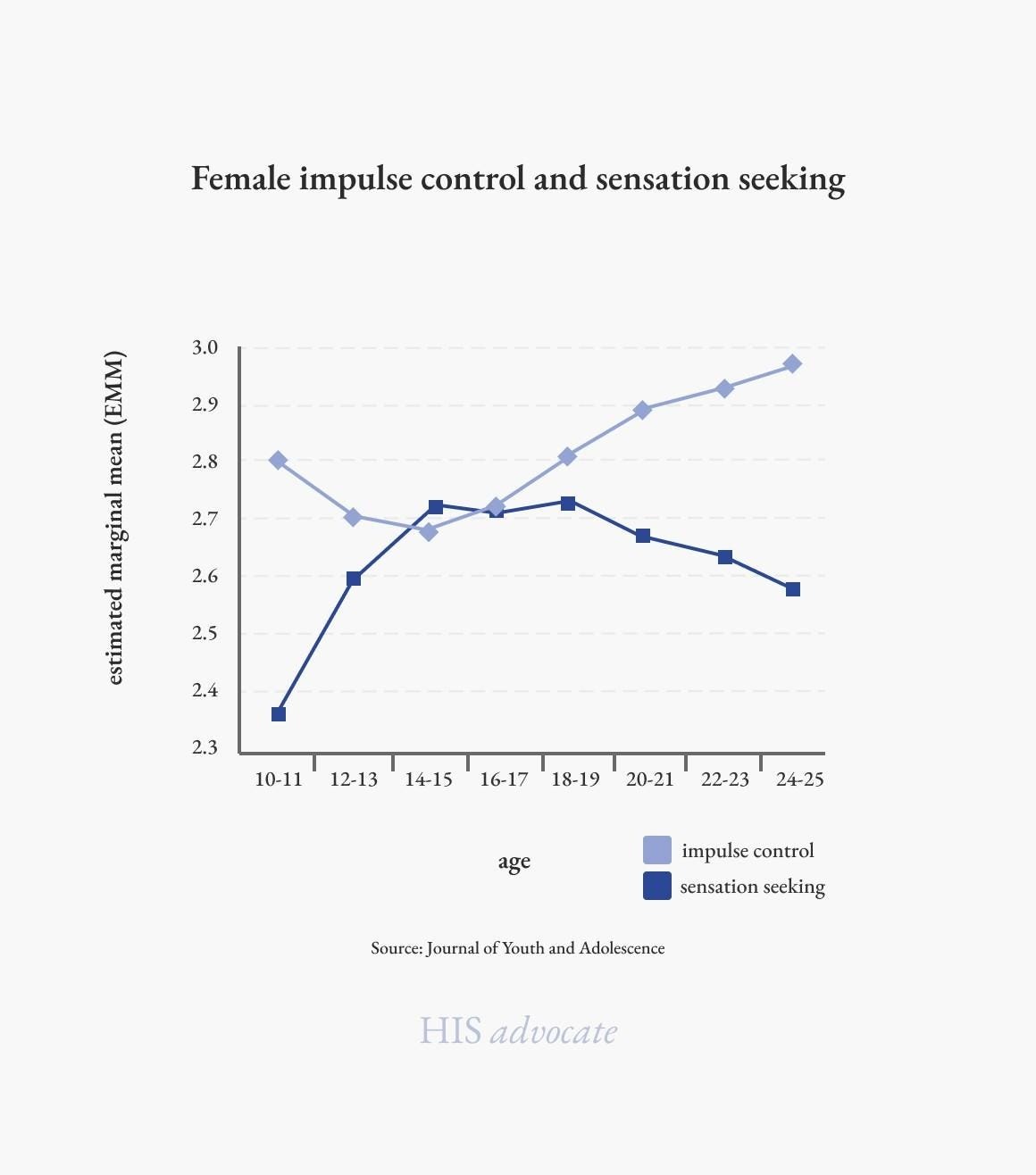

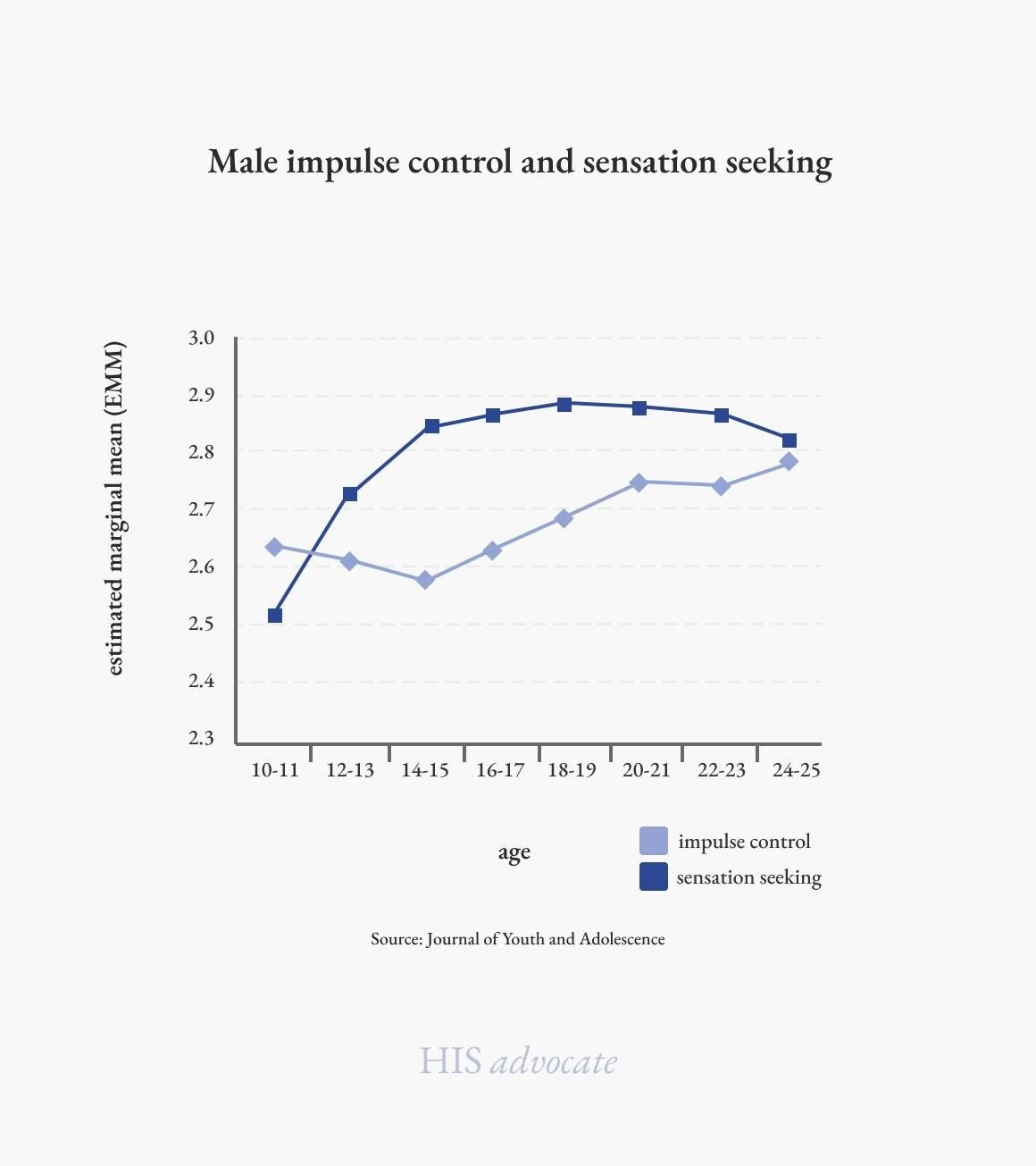

Would a boy play video games instead of studying for his upcoming math test? Is a girl more organized when she pulls out her binder at the beginning of class? These questions can be answered by looking at the prefrontal cortex. Often called the “CEO” of the brain, the prefrontal cortex is responsible for developing our impulse control and sensation seeking.16 In other words, this is the part of the brain where we weigh risks, delay gratification, and seek rewards. The two images below highlight the stark differences in how this area develops between boys and girls.

The prefrontal cortex matures two years earlier in girls compared to boys.17 From around age ten, girls consistently show strong self-control and delay gratification. Near age fourteen, their interest in thrill-seeking briefly increases, then quickly stabilizes, then their ability to delay gratification strengthens again around sixteen and continues increasing into their mid-twenties. In fact, the gap between self-control and thrill-seeking only widens after sixteen for girls.

For boys, the story looks very different, and it helps explain why they’re struggling in school. At age ten, boys’ impulse control is only slightly higher than their risk-taking tendencies. Around age twelve, risk-taking surpasses self-control and remains dominant until roughly twenty-five years old, when the gap finally begins to close.

The prefrontal cortex is also the part of our brain where we plan for our future. This explains why ninth grade boys “don’t know” what they want to be or why school feels irrelevant to them, to no fault of their own. By age sixteen, the developmental gap reaches its widest point between girls and boys. This is precisely the age in which students are preparing for SAT’s, exams, and when they begin to think about college. This gap that boys are experiencing makes it harder for them to meet classroom expectations of focusing and self-regulation. To put it another way, sitting still, paying attention, and staying quiet during class.

Other parts of the brain provide little relief for boys.

The cerebellum, located in the back of the brain, is linked to developing emotional regulation and cognitive abilities. It matures roughly at age eleven for girls, but not until fifteen for boys; a four year delay.18 Additionally, our brain goes through a “pruning” process, which refines and strengthens neural pathways. How does this process tie into an educational setting? The pruning process relates to sharper thinking, retaining, and recalling information better, which begins earlier in girls than in boys.

So what is the implication of all this? What does it mean for our society that our boys are falling behind in education? What will happen to them as young men navigating through college? How will they fare as men in society and what direction will they take?

The Cost of Falling Behind

I was an average student as a child. Not exceptional, or constantly struggling, but there were plenty of times when I failed homework, tests, and classes when report cards came out, and lacked the ability to focus. So at times, for example, when I couldn’t focus during math class at 8:00 a.m. in fifth grade, compounded with my other academic challenges, I began developing a belief that there was something wrong with me, that I was the problem, and that there couldn’t be any other explanation.

I took this belief into high school.

Sophomore year was my worst academic year ever. I stopped caring and trying in school altogether. I constantly skipped classes, I failed classes that I had to repeat the next year, and I was removed from advanced placement classes. Although things picked up by the time I graduated from high school, the damage was done. I was in the lower percentile of my graduating class, my GPA wasn’t great, and the most concerning part? I had no idea what I wanted to do in life.

It wasn’t until I was about 25 that I started to figure things out, and began to cram what I didn’t learn (delay gratification, applying myself, developing self-confidence), in an extremely short period of time.

I consider myself one of the lucky ones.

This isn’t about me; it’s that my story is shared by boys and men across the country. Now think of those boys and men in the hundreds of thousands, dare I say in the millions.

Boys have been wrongly labeled as careless or lazy for their lack of effort in school. But the reality is that they’re in a system that doesn’t align with their developmental timeline. The result of the developmental delay in boys means that they face challenges in managing their emotions, following rules, and staying organized during their early school years; this affects them well into their early twenties. Boys are judged on behaviors and abilities that are still developing or haven’t even fully developed yet.

Now imagine these boys growing up to become men without college degrees. How will they grapple with adulthood? Will they be able to provide for themselves, let alone a family? They’ll struggle finding high-paying jobs, which often require a college degree, and might find themselves struggling financially. This compounded effect is creating a societal pattern where large numbers of men are disadvantaged in multiple spheres of life.

The question is no longer whether it’s true that boys and men are falling behind in education, but why we’ve accepted it.

Supporting Our Boys and Men

It’s understandable why some argue that boys and men continue to have an advantage in education, even to this day, because they’ve always had the right to an education. It’s true that generally boys and men were never barred from education or opportunities in higher education.

But that’s optics.

It doesn’t factor the data showing us how boys and men are performing in school and the real-life consequences of underperforming; a reality that goes unnoticed. A group of people may have access to an opportunity, but that doesn’t negate the possibility of potential challenges that they may face due to external variables. Our assumption was that, since boys and men had the right to an education, they would never face problems in this regard; we never considered if outside factors would hinder boys and men in school.

When girls and women were underrepresented in different fields, programs, and higher education, we took action. Since then, we can see the results of how those actions helped women excel. Now, it’s time to extend that same principle to boys and men. If the data shows that they have fallen behind, we need to respond with the same urgency. Solutions such as male-only scholarships, incentives for entering female-dominated fields like HEAL, and new academic models that work with boys’ developmental timelines, not against them, are potential ways to address the education gap.

Some argue that helping boys and men comes at the expense of girls and women. This argument is based on a false premise. Supporting boys and men does not diminish or erase the progress made by girls and women. It simply acknowledges that both can be true; girls and women can thrive while boys and men receive the help they desperately need. We can celebrate the achievements of girls and women, while also recognizing that boys and men are struggling in ways society often ignores. We can value education for our daughters and sons because education matters for girls and boys.

For too long, we’ve blamed our boys for struggling in school and as Richard Reeves puts it, “…diagnosed them as malfunctioning girls.”19 In reality, the diagnosis is that our education system is broken and to blame for hindering our boys. Until we recognize this, we will continue to watch generation after generation of a system that will continue to fail our boys.

Noaman Farooq is an advocate and writer focusing on education, social trends, and challenges facing boys and men. He is based in Dallas, Texas, and you can follow his work on Instagram @his_advocate.

Disclaimer: Material published by Nuun Collective is meant to foster inquiry and rich discussion. The views, opinions, beliefs, or strategies represented in published media do not necessarily represent the views of Nuun Collective or any member thereof.

“Digest of Education Statistics.” IES, National Center for Education Statistics, Mar. 2016, nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_318.10.asp

National Girls Collaborative Project. “Connect, Create, And Collaborate to Transform Stem for All Youth.” NGCP, https://www.ngcproject.org/

Stem for Her. “Explore. Pursue. Engage.” https://stemforher.org/

Andara, Kennedy, et al. “Breadwinning Women Are a Lifeline for Their Families and the Economy.” Center for American Progress, 9 May 2025, www.americanprogress.org/article/breadwinning-women-are-a-lifeline-for-their-families- and-the-economy/

Gusto Insights Group. “2025 New Business Formation Report: Women Are on Par with Men as Side Hustles & Remote Work Decline.” Gusto, 3 Apr. 2025, gusto.com/resources/gusto-insights/new-business-formation-report-2025

Isaacs, Julia B. “Starting School at a Disadvantage: The School Readiness of Poor Children.” Center on Children and Families at BROOKINGS, Mar. 2012, www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/0319_school_disadvantage_isaacs.pdf

“Digest of Education Statistics.” IES, National Center for Education Statistics, Nov. 2019, nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_221.20.asp

Reeves, R. V. (2022). Of boys and men: why the modern male is struggling, why it matters, and what to do about it. Brookings Institution Press.

“High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09).” National Center for Education Statistics, nces.ed.gov/surveys/hsls09/

Bledsoe, I., Smith, B., & Scholl, B. (2025, June 24). What teens want to be: Gender differences in careers and majors. American Institute for Boys and Men. https://aibm.org/research/what-teens-want-to-be-gender-differences-in-careers-and-major s/

Cellini, Stephanie. “How Does Virtual Learning Impact Students in Higher Education?” Brookings, 13 Aug. 2021, www.brookings.edu/articles/how-does-virtual-learning-impact-students-in-higher-educati on/

Sax, Leonard. “Should Boys Start Kindergarten One Year Later than Girls?” Institute for Family Studies, 2 Nov. 2022, ifstudies.org/blog/should-boys-start-kindergarten-one-year-later-than-girls

Reeves, Richard V., and Will Secker. “Degrees of Difference: Male College Enrollment and Completion.” American Institute for Boys and Men, 29 Mar. 2024, aibm.org/research/male-college-enrollment-and-completion/

Reeves, R. V., & Smith, E. (2021, October 8). The male college crisis is not just in enrollment, but completion. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-male-college-crisis-is-not-just-in-enrollment-but-c ompletion/

Hawrami, R., & Williams, A. (2025, April 3). Major changes: Gender shifts in undergraduate studies over time. American Institute for Boys and Men. https://aibm.org/research/major-changes-gender-shifts-in-undergraduate-studies-over-tim e/

Akyurek, G. (2018). Executive Functions and Neurology in Children and Adolescents. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.78312

Brizendine, Louann. The Female Brain. 10th Anniversary Edition ed., Harmony Books, 7 Aug. 2007.

Lim, Sol, et al. “Preferential Detachment during Human Brain Development: Age- and Sex-Specific Structural Connectivity in Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) Data.” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 25, no. 6, 6 Jan. 2015, pp. 1477–1489, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bht333.

TED. (2023, June 21). How to Solve the Education Crisis for Boys and Men. [Video]. YouTube.

So obviously written by a man lol